Barcoding has become ubiquitous in supply chains that start at a manufacturing facility and end at a business or retail customer. Voluntary and regulatory initiatives are now extending barcoding further up the supply chain, to farms that grow fresh fruits and vegetables. The purpose of these initiatives is to support the reverse supply chain—i.e., recalls and traceability. But once farmers start using barcodes, they will likely find other productive uses for the technology and its supporting systems.

In the United States, the Food Safety Enhancement Act of 2009 (HR 2749) has passed the House, while the Senate version (S 510), which is similar to the House bill, is pending but said to be on the fast track. One of the features of this legislation is that it mandates end-to-end traceability of produce and other raw material inputs into processed foods (but not livestock and poultry).

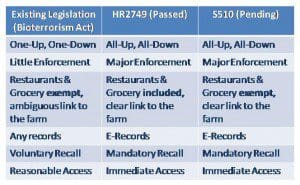

I am not fluent in legalese, so I find the diagram below useful. It summarizes how Gary Nowacki, the CEO of the traceability software company TraceGains, interprets the bill.

The “one-up, one-down” recordkeeping mandated by the U.S. Bioterrorism Act of 2002 requires that every handler of food products establish and maintain records to document the movement of its products both one step forward and one step back through the supply chain. This includes the immediate source of all food and ingredients received and the immediate subsequent recipients of all food and ingredients released. “All-up, all-down” would require a mechanism for near instantaneous end-to-end traceability, clearly a much more difficult task to accomplish.

It should not come as a surprise to anybody that industry groups prefer the existing legislation to the pending one. They particularly don’t like the penalties. In HR 2749, unintentional violations can lead to penalties of between $250,000 and $1 million; intentional violations can result in imprisonment for up to ten years. Enter stage right the Produce Traceability Initiative (PTI) sponsored by the Canadian Produce Marketing Association, the Produce Marketing Association, and United Fresh Produce Association. The guidelines proposed in PTI would improve current produce traceability capabilities, but they fall short of the requirements outlined in the new legislation. PTI seeks to build better transparency based on a common nomenclature for case labeling.

The standards for case tracking would be based on GS1 Global Trade Identification Numbers (GTINs). GS1 is a not-for-profit, global standards organization responsible for creating standards for RFID, EDI, UPC barcodes and global data synchronization.

You can visit the PTI website if you want to dive into the seven step PTI process, but here are my key takeaways:

- There are some big companies participating in this initiative: retailers such as Wal-Mart and Kroger; wholesalers like Sysco and U.S. Foodservice; and third party logistics firms like C.H. Robinson. However, this is a voluntary program, and while some large growers are participating, the majority are not.

- Brand owners are expected to obtain GTINs to enable case tracking. A brand owner includes growers or shippers who wish to maintain their own brand; packers that change the composition of the original case or product and re-brand; and buyers requiring private labeled product. However, because case traceability often starts with a packer, I can still see situations where traceability is difficult. Imagine cases arriving at a packer’s facility, being dumped on a conveyor, and the produce being sorted and graded. In this scenario, the case being shipped out could contain produce from many farms, so tracing a pathogen back to a particular farm would still be difficult.

- There are a series of steps for those in the program. Some steps are expected to have occurred already, while others are occurring right now, in the third quarter (harvest time) 2009. But all the steps won’t be completed until 2011.

- This is “one-up/one-down,” not “all-up/all-down” traceability. Each subsequent handler of a case of produce will have the systems and capability to read and store the GTIN and lot number from each case of produce received. However, the final step in the program pertains to reading and storing information about outbound cases. The way I read this is that retail recipients of this information are not being asked to store it.

Gary makes the point that once growers start using bar codes and handheld computers with scanners, traceability data could be enriched by capturing additional attributes, such as GPS, when a pesticide or fertilizer is applied, and when the field is irrigated, that would help growers better manage their farms for profitability.

Leave a Reply