When Russia invaded Ukraine, I knew there would be impacts on global supply chains. But supply chain impacts like the rising cost of gas, or the inability of a train to cross Siberia to bring goods from China to Europe, or the increased congestion this would cause at China ports, was not the supply chain impact I feared most. What I most feared was cyberwar.

The Cyber Supply Chain

I feared this because I’d been reading Nicole Perlroth’s book, They Tell Me This is How the World Ends. The book won the FT & McKinsey Business Book of the Year Award in 2021. Ms. Perlroth covers cybersecurity and digital espionage for The New York Times. She has covered Russian hacks of nuclear plants, airports, and elections; North Korea’s cyberattacks against movie studios, banks and hospitals; Iranian attacks on oil companies, banks and the Trump campaign; and hundreds of Chinese cyberattacks and their ongoing success in stealing intellectual property from multinationals.

I came away from the book with the frightening realization that if a nation state with advanced cyber capabilities wants to hack a corporation, they can. And a hack does not just mean data is stolen, it could be critical information is held hostage or destroyed. There is almost nothing the company can do to stop a well-funded nation state intent on these kinds of attacks. There are several reasons for this that are beyond the scope of this article. But because my coverage is focused on supply chain management, I will discuss that.

The servers, computers, tablets, and smartphones we use are built in global supply chains with components and assembly taking place in many countries. In 2018 it was reported, for example, than an iPhone is assembled by workers at Foxconn’s factory in the Chinese city of Zhengzhou; and made of raw materials and components sourced from 43 nations. An unfriendly nation could require that the components or assembly of computer components taking place within their domain contain “backdoors” that can be exploited for cyber spying or attacks. Further, certain types of “zero-day” exploits, those built into the hardware as opposed to the software, are virtually undetectable. But even if a nation state does not require backdoors, there are many employees across many nations that can be bribed or coerced by malign actors to cyber compromise the components they are building.

Sid Snitkin, the vice president of cyber protection advisory services at the ARC Advisory Group, says that the supply chain for software is even more vulnerable. “When I was younger, I did programing. Every line of code for an application would be written by me or a colleague. Now an application is written by folks that grab a piece of code from here or a piece from there. Hackers attack small suppliers. They embed malware in the code. Then when an IT professional gets a message to update the software, the software is contaminated. It is almost impossible to check whether all these small pieces of code are clean.”

The Nation’s Efforts to Strengthen Cybersecurity

Last May, the Biden administration issued an executive order on improving the nation’s cybersecurity. There were several fine prescriptions in this order, but the order was much more focused on improving cyber security for the federal government than for private companies.

More recently, on March 21st of this year, President Biden made a statement on our nation’s cybersecurity. An accompanying fact sheet had several best practices companies should follow. These best practices, however, were a better prescription for companies running on-premise applications than the newest generation of Cloud solutions.

Increasingly, companies core applications are hosted in public clouds run by Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, Google and others. The tech companies running these public clouds argue that the cyber security they provide exceeds anything private companies could hope to achieve. That is undoubtedly true. But if one takes the perspective that a nation state that wants to cyber attack these Cloud solutions, they could succeed. Further, taking down a public cloud like these would compromise hundreds, or even thousands of companies, core data. As such, these public clouds, while harder to hack, are a much more enticing attack vector.

Detection and Response

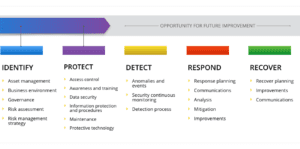

Mr. Snitkin agreed that if a nation state wanted to compromise public clouds they could. However, he said, that the philosophy undergirding cyber security has changed. “Rapid detection and response is all you can do today. He also noted that AWS, Oracle, and Google will all be backing up their data.”

But what if an attack is at the hardware level and almost impossible to detect? Mr. Snitkin acknowledged that some viruses introduced into a PC can embed itself in the firmware. Even if a company erases the software and reloads it, the virus still exists. This Shamoon virus that attacked Saudi Aramco in 2018 was an example of this. All the PCs had to be destroyed and new ones deployed. This took days. “You have to get clean before you can start up again,” Mr. Snitkin explained.

It was a similar story for Maersk, the largest shipper of containers in the world. Maersk IT systems were the victim of a malware attack utilizing NotPetya, which perpetrated by the Russian military to attack Ukraine, but in fact also hit Maersk hard. All end-user devices, including 49,000 laptops and print capability, had to be destroyed. All of the company’s 1,200 applications were inaccessible and approximately 1,000 were destroyed. Data was preserved on back-ups, but the applications themselves couldn’t be restored from those backups as they would immediately have been re-infected. Around 3,500 of the company’s 6,200 servers were destroyed and could not be reinstalled. It took two weeks to restore all the global applications. But Maersk, as even Maersk admitted, did not have a robust cyber defense strategy in place.

Mr. Snitkin is convinced that the big Public Cloud companies would be able to backup their customer’s core data and use security solutions like data diodes to ensure that it remains beyond the reach of malicious actors; but the process of restoring the data in clean servers could take as long as days.

That reality makes one best practice particularly important; companies should have emergency plans in place. Further, companies need to run exercises and drill on these emergency plans so that their people are prepared to respond quickly to minimize the impact of any attack. And if a company has critical partners – suppliers, contract manufacturers, and logistics service providers – than your company should make sure they also have these emergency plans and practice drills in place.