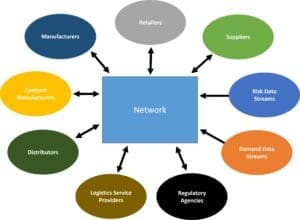

ARC has done research and writing on supply chain collaboration networks. A supply chain collaboration network (SCCN) is a key technology for improved collaboration across an extended supply chain. SCCN is a collaborative solution for supply chain processes built on a public cloud – many-to-many architecture – which supports a community of trading partners and third-party data feeds. SCCN solutions provide supply chain visibility and analytics across an extended supply chain. Networked applications have distinctive advantages that other types of solutions lack.

But when ARC has done writing on SCCN, we have written about how this solution set can help a company optimize its own supply chain operations. That is how enterprise and supply chain software solutions work. A company buys these solutions to optimize their business.

In a conversation with executives from Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), they flipped the conversation. Instead of thinking about planning from a company point of view, companies should consider driving efficiencies across their extended ecosystem value chain. What ARC calls “supply chain collaboration networks,” TCS refers to as “ecosystem commerce platforms.”

Rich Sherman – a Senior Fellow in TCS’s Supply Chain Center of Excellence – points out that many companies are building control towers to better manage their supply chains. In contrast, an airport has a control tower, but it is used to help manage all the flights from all the airlines coming into an airport. “The emerging issue is that while internal control towers have visibility and control over their loads, they don’t have visibility to all of the loads in the market ecosystem in which they operate.”

It is not just continually changing demand and material and equipment constraints across a company’s value chain that matters. It is these changing constraints, transportation capacity, and bottlenecks across an entire ecosystem that matters. The lack of predictability leads to higher costs and worse service. And this has clearly gotten worse in recent years.

“Companies,” Mr. Sherman points out, “are realizing that their supply chain is not really a chain at all.” They have a complex network of suppliers, internal assets, and transportation and manufacturing partners, many of whom are changing on an ongoing basis. The network a company gains visibility to with their control tower is just one of many networks.

SCCN suppliers like Emerge, GEP, and Coupa provide good network visibility to procurement; solutions from FourKites and project44 provide visibility to shipments; and solutions from Interos or Eversteam Analytics provide visibility to new risks in almost real time. And there are other types of supply chain collaboration networks as well. So, Mr. Sherman believes we need to start thinking about a “network of networks community” that is comprised of all the participants in the market ecosystem. This would include not only a company’s own trading partners but their supplier’s suppliers, their customer’s customers, and their competitor’s extended value chains. If, for example, there had been better ecosystem visibility to longer term semiconductor demand, then we would not have had the kind of chip shortages that many industries continue to struggle with.

TCS believes that once broader network visibility is available, companies can think of planning in a new way. Traditional enterprise resource planning and supply chain planning applications plan from the inside out. In other works, based on the data in their internal systems and rather limited collaboration, they optimize their internal operations. But something called ERP 4.0 will lead to ecosystem planning and optimization application suites.

In supply chain we talk about the fact that just optimizing one link in a chain – for example, optimizing manufacturing – does not lead to an optimized system. Supply chain planning systems can optimize across a company’s whole interconnected set of sourcing, manufacturing, and distribution operations. Saving money in manufacturing operations does not necessarily lead to saving the most money across the entire interconnected system.

That same argument can be made for an ecosystem approach to planning. Optimizing the ecosystem can lead to savings for every participant in the ecosystem that exceed what an individual company could achieve using a “me first” planning approach.

This is a breath-taking vision. Making the vision a reality will be difficult. This is such a fundamental rethinking of supply chain management that the initial reaction of many practitioners will be that this could never work. But recent history has shown us that the current approach to supply chain management is broken. Just when Covid shocks begin to recede, inflation and war are creating new shocks. Almost no supply chain executive believes that the kind of predictable, stable supply chains of former times are coming back in the foreseeable future. Clearly, a new approach is needed.

Achieving ecosystem planning probably can’t be done in one big leap. Mr. Sherman says companies need to know when to cooperate and know when to compete. For example, many companies are struggling to get transportation capacity. Meanwhile, waste is rampant in the freight industry. This occurs when truckers drive empty, typically because there are no nearby loads for the driver to pick up that are headed in the same direction as the driver. In the freight industry, these are referred to as empty miles. These miles mean that drivers are not earning money for being on the road and shippers pay more to move goods. Roughly 30% of miles driven are empty miles. This is an ecosystem problem. Perhaps this is the first ecosystem network battle to be won in a larger war to achieve new supply chain efficiencies.