Yesterday and today, Blue Yonder, the former JDA, had their annual user conference. The pandemic led to its being held on-line.

BD’s Eric Miller, the Senior Director of Global Logistics Solutions and Optimization, was one of two BD executives that spoke on their implementation of a global control tower. BD, with annual revenues of approximately $16 billion, is a leading global medical technology company. They have a broad set of products. This includes solutions used in COVID-19 research, a product that tests for COVID-19, and other products used for treating hospital patients. 90 percent of those in the US who go into a hospital will encounter a BD product.

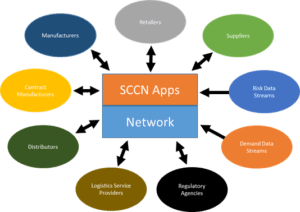

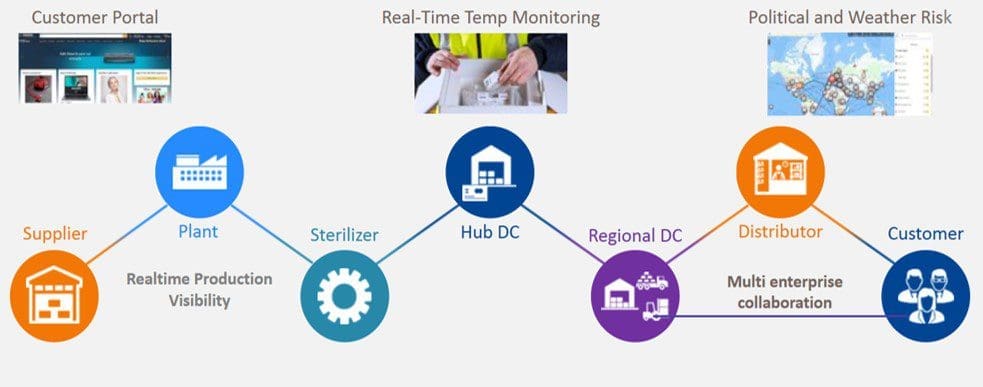

Mr. Miller defined their digital transformation as a “physi-digital” journey. This is defined as a best in class physical chain, enhanced and accelerated with digital capabilities. From a visibility perspective, the goal of the project was to track every unit, everywhere, in near real-time, across an end-to-end supply chain using the control tower as the one source of truth. This visibility, in turn, is seen as being critical to better serving customers – getting them products when they are promised or advance notification when that is not possible. End-to-end visibility also allows for cost savings and new supply chain efficiencies based on better collaboration.

Digital is Key to Customer Responsiveness

Mr. Miller pointed out that we are living through the largest supply chain disruption in history. “BD is no stranger to supply chain disruptions” whether they are caused by mergers, port closings, hurricanes, or in this case, by a global pandemic. “We’ve had them in the past. We will have them in the future.” But they are becoming more frequent and more disruptive. For this reason, digital transformations are even more important.

The company is building their control tower in three phases. They have finished phase one and are well into phase two. Because they employed an agile methodology, they were able to pull functionality needed during this pandemic up from phase three. This feature set allows BD to track critical pandemic items shipped via FedEx to customer locations.

One customer desperately needed BD supplies and called the company up and asked why the goods had not shipped. An analyst on the COVID response team was able to see that the products were sitting on a carrier’s dock waiting for an appointment at the customer’s site. They put the customer and carrier together and the situation was quickly resolved.

A few weeks ago, BD had an issue with containers on an ocean vessel traveling from Freeport in the Bahamas to Le Havre France. 28 of their containers were thrown overboard after the ship declared ‘general average’ due to problems with the ship’s rudder. General average is a principle of maritime law whereby all stakeholders in a sea venture proportionally share any losses resulting from a voluntary sacrifice of a ship’s cargo to save the vessel in an emergency. That same ship was scheduled to carry two more BD containers on the return trip.

BD needed to know the impact for insurance and legal reasons. But more important, they needed to understand the impact to their supply chain. What customer orders might not be fulfilled? Did BD have enough product to cover demand? Would they need to use air freight to rush product to customers? Mr. Miller stated that those questions were answered in minutes because of their control tower technology.

Digital Control Towers Drive Supply Chain Efficiencies

Mr. Miller said that several years ago he took over leadership of a global planning team. The team was facing product supply shortages and was trying to discover if, and how, they could meet the business unit’s financial goals. Mr. Miller turned to his best planner. He asked her, “where are we and what can we do? It took two days. “It was great analysis.” But there were places where there were information black holes. They had no in-transit information, no information on their inventory position in China, which was on a different business system. The data situation was not much better in Europe. “We worked for days to pull together all this data across regions and sites.” And even with all this effort, the plan was only 80 percent complete. “I asked myself, is this really the best use of our time? Is there a better way?”

Their control tower project is providing the kind of real-time information Mr. Miller had dreamed about. He gave the example of a supply chain analyst based in Latin America that discovered a regular air freight shipment was a waste of money. Air freight is very expensive. The analyst was able to view the actual transit time on this lane. Based on the actual transit time, it was clear air freight was not providing the service they had thought. BD was able to maintain a high level of customer service while saving $65,000. The control tower pulls planning and logistics data together in a manner that makes these kinds of decesions possible.

BD Control Tower Capabilities

BD’s control tower has a range of important capabilities. Some of these capabilities are live now. Others are scheduled to be live by the end of the year. And, BD believes that machine learning applied to Big Data will allow the solution to automate more and more decisions over time. The solution can already save hours or even days of work, but the automation will continue to improve.

The solution surfaces near real-time exceptions. It then allows for smart resolutions to oversupppy, back orders, and to supply disruptions. In some cases the playbook allows an analyst to immediatley resolve the exception. If not, it It provides robust collaboration capabilities across regions and functional groups that lead to faster resolutions than was previously possible.

The control tower will provide more timely information to customers. And it empowers planners to meet customer expectations. Analysts can filter for specific products and track shipment statuses. The system can flag ‘hot’ items – items that are close to stocking out at a final stocking destination – and then resolve that problem with a few clincks.

In short, this technology provides a strong foundation for the customer centric supply chain of the future that BD is building as part of their digital transformation. This article discussed the benefits flowing from BD’s digital control tower, including the value it has brought during this pandemic. A follow-up article on the BD implementation will provide important insights for companies thinking about implementing their own control tower.