When it comes to creating labor standards for the warehouse, both time studies and predetermined time systems (PTS) appear to create highly accurate and granular labor standards. But how objective are they really?

The truth is that there is some subjectivity associated with time studies and PTS. Time studies have something called “pace and skill ratings” that consultants use to normalize the raw stopwatch data. If a worker takes 100 seconds to complete a task, it does not mean that 100 seconds should be the standard for that task. Consultants must also judge whether the associate was following best practices and whether they were working slowly or at a reasonable pace. If in their judgment the associate was a bit clumsy and slow, they might decide that 100 seconds represents a 50 percent effort—i.e., that instead of using 100 seconds as the standard, it should be 50 seconds. Labor standard consulting firms recognize that there is some subjectivity in this approach, so they try to compensate for this by observing a process performed multiple times by different associates. Charlie Zosel of TZA mentioned that his firm typically does two or three days of observations for an activity such as picking a case to a pallet. For a warehouse with many different SKUs and processes, this could translate into a 4 or 5 month effort for the warehouse as a whole.

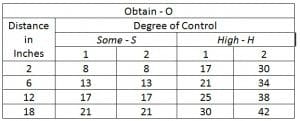

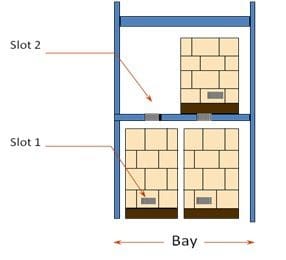

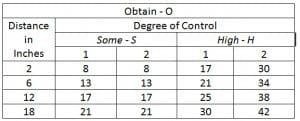

MSD and MOST are the two most prevalent methodologies used to develop PTS time standards for the warehouse. PTS seems more objective than time studies, but some judgment calls are still required. If you were to examine a MDS time standard card for an “obtain” motion (e.g., grab and gain control of a case), you would see that the industrial engineer (IE) needs to judge the “degree of control.” While the MSD handbook explains how you should go about judging degree of control, it still creates difficulties for new industrial engineers. One of the subject matter experts I interviewed said that the first time an IE does a PTS study, 25 percent of the standards they develop are wrong.

The degree of judgment tends to be smaller in repetitive manufacturing environments. For example, imagine pencil manufacturing. A person sits in the same location and does the same series of things, time after time, with very small variations depending on the lot. Now imagine grabbing a case (OBTAIN) and putting it on a pallet. The warehouse could have 500,000 SKUs and cases varying in weight and dimensions. IEs deal with this scenario by grouping SKUs into different classes depending on weight and dimensions. Charlie says this methodology works very well for full-case pick or kitting, but is less effective for broken-case picking, and even less effective in receiving. Different processes in the warehouse inherently have different degrees of variability.

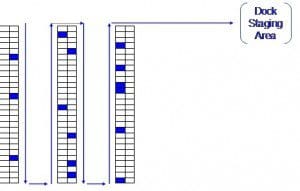

Further, with PTS, you still need to build “frequencies and branches” off those standards. For example, if a worker is traveling to a slot, what do they do if the aisle is full? They could wait or they could go to the next aisle and come down the far side. How often does that happen? How often does a supervisor stop a worker to talk to them? What if the slot is not full? IEs recognize that a certain amount of slack needs to be built into their standards to cover these contingencies. This is called “work sampling” or a “frequency delay analysis.” An IE follows workers around and ticks off the delays. A warehouse’s standards can get ruined here. An IE can do a very thorough and detailed MDS or MOST analysis and then spend only a few hours on the frequency delay analysis. They can end up determining too quickly that all standards should be adjusted down 7 percent, when perhaps a more detailed analysis would have showed that a 5 percent adjustment would have been more accurate.

Finally, developing a fair standard using PTS is difficult when multitasking is involved. For example, imagine a worker peeling a label while walking to a slot. PTS can develop a standard for peeling the label and for walking to the slot, but if both are done simultaneously, what should the standard be?

Actually, consultants who have experience with both time studies and PTS can develop more objective standards by employing a different methodology to double check questionable standards. If both the time study and the MSD or MOST methods return very close to the same number, you have a good number. Some consulting organizations, like TZA, formally use this hybrid approach. At other organizations, experienced consultants use this hybrid approach almost instinctively.

Further, while this article has identified more areas of subjectivity with PTS than with time and motion, the subjectivity involved with a time study’s “pace and skill” ratings is potentially more troubling. In fact, many consulting organizations believe young industrial engineers will develop better standards with PTS than time and motion because learning “pace and skill” is an art that’s not easy to learn.

The point of this article is not that warehouse labor standards are inherently inaccurate. That would be untrue. Both PTS and time studies can result in very accurate standards that consistently stand up to legal challenges. But a potential purchaser of a time study consulting engagement should be aware of the places where subjectivity can be introduced into the process and take steps to avoid it.