The law firm Crowell & Moring recently released a survey-based report that looked at how companies are navigating pressures to improve their environmental performance. The company surveyed 225 executives whose jobs included environmental, social, and governance issues. 56% of respondents said their company does NOT measure its carbon footprint.

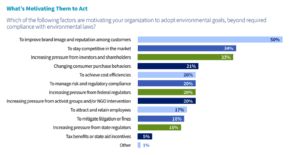

What may surprise many people is that increasing pressure from investors is the third most common reason – cited by one third of respondents – for companies to adopt environmental goals. Afterall, investors only care about the bottom line, right? It turns out, pension funds often approach investing differently.

Pension Funds are Focusing on Carbon Emissions

Mutual Funds that are actively managed try to pick firms that will be winners. They seek to understand the upside potential and the downside risks of individual firms.

Pension funds are different, they are so big that they invest in whole sectors. The Japanese pension fund, the Government Investment Pension Fund (GPIF), owns 7% of the Japanese equity market and about 1% of the world’s equity. Pensions often invest in multiple passive funds. These passive funds hold every available stock in an industry or class of investments. These sector specific funds are designed to track that performance of that whole swath of firms, not to beat the market. So, for a pension fund, the main risks are not company specific risks, but systemic risks. Systemic risks are so large that virtually every firm will be negatively affected if that class of risk manifests itself.

For pension funds, one of the largest systemic risks is the risk of climate change. Sustained climate change could lead to a world in which almost all firms perform worse. In effect, some pension funds, seek to improve the performance of the pension by lowering risks across the entire economy.

Here is how the Norwegian pension fund explains it: “Our motivation for responsible investment is to achieve the highest possible return with moderate risk. Companies’ activities have a considerable impact on society and the environment around them. Over time, this could affect their profitability and so the fund’s return. We therefore consider both governance and sustainability issues and publish clear expectations of companies in the portfolio.”

The Japanese pension asks every one of their asset managers to start having systematic conversations with every company they invest in about that company’s approach to environmental, social, and governance issues. Companies not making progress might face the pension fund voting against the existing management of a company at a proxy election.

Crawl, Walk, Run

When a company initially sets goals for reductions in their carbon emissions, they find a lot of low handing fruit. A company might decide to invest in a more energy efficient machine. Thus, the company gets energy savings and carbon emission reductions. Or they might invest in a type of supply chain software, like transportation management, that gets them strong freight savings while simultaneously lowering their carbon emissions.

Sometimes companies embarking on a sustainability initiative will require a lower return (less savings per dollar invested) for ESG initiatives than for other capital investments. But they still expect savings. They still want a good payback on the investment.

But eventually, if carbon reduction goals are at all significant, companies will face tradeoffs. Lowering carbon emissions will require greater costs.

Supply Chain Planning Solutions are Trade Off Machines

Existing SCP solutions can generate a plan, for example, that leads to the lowest costs that allow the firm to deliver a 95% service level to their customers but do so in the most cost-efficient manner.

Now, SCP companies are being asked to add CO2 emissions as a third goal to plan around. So, the goal might be to develop the least cost plan that delivers a 97% service level while keeping emissions under some defined target. This may sound simple. It is not!

It is hard to describe just how complex supply chain planning solutions can get. A SCP solution creates a model of a supply chain. A factory planning solution, for example, might model the throughput of every machine on a factory line, which products can be made on different machines, how the factory throughput is affected by the route the product takes through the factory while being built, and so many other things. A million different schedules might be examined, in a matter of seconds, before the optimal plan is selected. I have greatly simplified what these models contain for the purpose of making these solutions a bit more comprehensible. An end-to-end supply chain model that encompasses sourcing options through to manufacturing and finally out to customer deliveries can contain more than a million variables!

Now, next generation planning models will need to understand the constraints and attributes associated with carbon emissions. I have kicked off research on the SCP market and am talking to executives across the industry. So far, I have talked to executives at Kinaxis, John Galt Solutions, Starboard Solutions, Adexa, and Honeywell. All are adding carbon optimization capabilities at the behest of their customers. Praveen Sam, a director of product management at Honeywell Connected Enterprise, said that it was pressure from the financial community that led one of their more important customers to ask for this new functionality.

Are manufacturers engaged in tradeoffs where they are accepting higher costs to reduce emissions? The SCP executives I talked to say their customers are at the beginning of the journey. First, their customers seek to document what their emissions are. Next, the customers seek to show what the tradeoffs would be from a cost perspective if the company did put in place an optimal plan to achieve targeted reductions in emissions. The expectation is that initially companies will NOT engage in a tradeoff; they will select the lowest cost plan.

But it is important that companies be able to show the financial community they are making progress, year after year after year. In the early years, progress can be made without tradeoffs. But eventually, these tradeoffs will need to occur, and companies must be in a place where the tradeoffs can be made optimally.

Finally, the financial community also wants to make sure the progress on sustainability that companies are reporting to them is real. When public companies release their financial results, the results are audited by certified public accounting firms so that the public can have faith in what is reported. A similar thing is occurring around ESG reports. We are beginning to see them certified by third party auditors.