The logistics industry is obviously interested in what sorts of taxes might be applied to fuels that emit carbon dioxide (CO2). Whatever laws are enacted will depend partly on the public’s opinion on these issues. Recent surveys show somewhat contradictory reactions in the American public as to whether green house gases are causing global warming, and if so, what should be done about it.

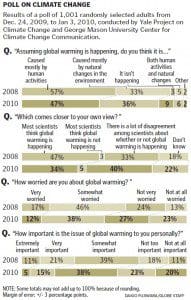

A recent poll by the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and George Mason University, conducted December 24th 2009 through January 3rd 2010, shows a decline in public concern about global warming (see “After errors, global warming gets a cold shoulder,” Beth Daley, Boston Globe, March 8, 2010). This poll of more than 1,000 randomly selected respondents had 50 percent of the respondents saying they are “somewhat’’ or “very worried’’ about global warming. However, this was a 13-point decrease from the fall of 2008. Sixteen percent of the respondents believe that global warming isn’t happening and is probably a hoax, up from 7 percent in 2008.

This decline could be explained by the “Climategate’’ controversy, which skeptics publicized late last year as evidence that global warming data is not credible. Or it could be explained by an unusually cold and snowy winter in much of the U.S. For the first time in recorded U.S. weather history, snow was on the ground in all 50 states last month. Or it could be that economic pressure is leading some in the public to put more focus on their own economic interests.

Meanwhile, a report by the Pew Research Center points in the opposite direction. Their survey included almost 1,400 respondents and was conducted from February 3-9 2010. A majority (52%) of Americans favor setting limits on carbon dioxide emissions and making companies pay for their emissions, even if it may mean higher energy prices; about a third (35%) oppose the proposal. In this case, the number of respondents in favor of setting limits actually increased by two percentage points since the last survey was conducted in October 2009. However, as was the case in October, those who have heard a lot about the legislation are more likely to oppose it (54%) than those who have heard a little (27%) or nothing at all (36%).

Most economists believe that if your goal is to reduce CO2 emissions, a carbon tax makes more sense than cap and trade. Cap and trade is, in reality, an indirect tax on the public. Carbon taxes on fuel would work best if: (1) fleet owners are provided invoices that clearly separate the carbon tax from the fuel sales tax; and (2) they are fairly constructed, meaning that fuels that emit more CO2 (diesel) are taxed at a higher rate than less polluting types of fuel (gasoline).

While a direct tax would send a clear signal to fleet owners, it would take several years, perhaps as long as a decade depending on how big the tax was, to replace inefficient trucks with newer models. This is another way of saying that the price elasticity of fuel is low, that upward changes on price have a relatively small effect on the quantity bought. Thus, any carbon tax should be combined with tax incentives to buy newer trucks. Further, early introduction of cleaner engines could also be stimulated by financial instruments such as preferential road toll rates. In Germany, for example, road toll discounts were introduced in 2005 which stimulated early launch of trucks that complied with Euro 5 emission standards.