I recently wrote about some of the thinking and core concepts behind achieving the lowest supply chain costs in a Direct Store Delivery (DSD) supply chain (see “Direct Store Deliveries and Lowest Total Supply Chain Costs”). Today, I will highlight how Coca-Cola Enterprises (CCE) has actually put these concepts into practice. I’d like to thank Mike Jacks, Sr. Manager for Logistics Systems at CCE, and Brian Wilkie and Brian Crane, Logistics Business Analysts, for taking the time to walk me through their process.

Coca-Cola Enterprises, based in Atlanta, Georgia, is the Coca-Cola Company’s largest bottler. Its products include carbonated beverages, like Coca-Cola and Diet Coke, as well as energy drinks, bottled water, teas, and juices (e.g., Powerade, Dasani, Gold Peak and Minute Maid).

Historically, a large part of CCE’s fleet was composed of side-load trucks that were loaded with several full pallets of the same stock keeping unit (SKU). As products proliferated, CCE found that for many stores it was no longer possible to load full pallets of a single SKU. The company went from delivering 12-15 SKUs per order to dozens of SKUs. Further, as more retail chains started using EDI for purchase orders and for receiving advanced shipping notices (ASNs), CCE found that these retailers were less likely to place orders that supported “main loading” (bulk picking).

A traditional DSD beverage delivery system relies on side-load vehicles with 10-16 bays. A side-load truck would visit several stores, and at each stop, the driver would stock the shelves with whatever product that store ordered. The warehouses would pick enough pallets of a SKU to support all of the stops. In effect, the driver became the order picker. He would open one bay and select the cases off one pallet, open another door and pick the cases needed of a second product, and so forth until the store’s order was complete.

Now, however, because of continued SKU proliferation (selling not just carbonated drinks, but all those power drinks and juices too), CCE is increasingly “pocket loading”—i.e., picking by order by stop. In other words, CCE is building mixed-SKU pallets that have the various products, in the right quantities, necessary to fulfill a particular store’s order. CCE is using two solutions from Ortec to help it build these pallets. These solutions help CCE decide which products to load on which trucks, which trucks should visit which stores, and then determine how to build pallets efficiently. The pallet-building logic takes into account case dimensions, product crushability, and product affinities (i.e., ideally, products that are located near each other in the warehouse should be picked onto the same pallet to minimize the travel time of pickers).

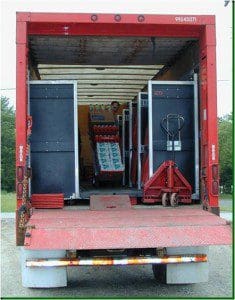

To better support store-level picking, CCE began buying 28-ft.and 35-ft. order fulfillment system (OFS) trucks eight years ago. These trucks have rear-loading doors and are wider than standard bulk-delivery trailers, so they have enough space for a narrow aisle up the middle for the driver to walk down. These trucks allow CCE to load a store’s orders into specially built carts that are fastened to the sides of their trucks.

While these trucks are reverse loaded (the order for the first stop is loaded last), the middle aisle supports flexible delivery sequencing. If a driver gets to a store whose dock is full, he can skip that stop. The middle aisle allows the driver to select the next store’s orders without having to shuffle goods around inside the truck.

OFS trucks will not fully replace CCE’s side-load trucks. In some metropolitan areas, the OFS trucks are too wide for the narrow streets. However, OFS trucks have a number of advantages. Many are hybrid trucks with Eaton engines that are 30 percent more fuel efficient than traditional trucks. CCE believes it has the largest hybrid fleet in North America. Another advantage is that while these trucks support store-specific carts, they can also be loaded with palletized orders for large customer deliveries.

Building customer-specific mixed-SKU pallets in the DC is more expensive for the warehouse. But CCE’s time and motion studies show that its overall end-to-end costs are lower because its drivers are more productive. Further, OFS trucks allow CCE to hire more experienced drivers, and because their job is easier, driver retention is improved. Drivers also don’t have to do as much product lifting or have to open and close many bay doors, making them less prone to injury. While the recession has made hiring and retaining drivers easier, CCE expects this will be a challenge again once the economy recovers.

In short, better thinking about what kinds of trucks it needed in its fleet has allowed CCE to do a better job of optimizing its end-to-end supply chain.