Stanley Black & Decker is a $9 billion hardware and home improvement manufacturer. Carl focused his talk on the Kwikset (locksets, door knobs) and Price Pfister (faucets, showerheads) brands. Sixty percent of the sales of these products come from “Big Box” retailers like Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Menards. Surprisingly, these products are style sensitive—i.e., 33 percent of their revenues come from products introduced in the last three years. This volume of new product introductions greatly increases the risks associated with excess and obsolete (E&O) inventory.

The Big Box channel includes retail chains with thousands of stores, representing different regions and target customers with different tastes. Stores vary in size, product velocity and geographic location. This leads to very different product mixes and varying aisle configurations (6, 7, or 8 bay sets, for example). Making channel management even more difficult is that the company ships to retailer distribution centers for some chains, while for others it ships direct to store or to transit facilities. Some retailers engage in centralized buying, while others have very decentralized processes. And some retailers demand exclusive SKUs.

The Big Box channel can be a significant source of E&O inventory. If demand for a new product introduction is misjudged, it is unlikely that other markets will be able to sell the excess inventory. Further, Stanley Black & Decker sources many of its products from Asia, so order-to-shipment lead times are four to six weeks. As a result, the company keeps 15 to 20 weeks of inventory for many SKUs to meet its service levels goals.

2007 was the watershed year, a bad year for the company in terms of excess and obsolete inventory. Consequently, the company formed an E&O reduction team, which identified four areas for process improvement:

- New product introductions (NPI): the company needed a more disciplined approach to NPI from the very inception of the product;

- The company needed to more efficiently transition out of obsolete inventory by better managing the drawdown of inventory as the SKUs matured (a glide path to zero inventory);

- Following the drawdown, if the company was left with excess inventory, it needed to improve and accelerate the efficiency of its disposition process;

- The company needed an early warning system about underperforming SKUs, with defined corrective actions. This was the area that Carl spoke mainly about in his presentation.

The first step in developing a better early warning system was to come to an agreement with sales and marketing on how to rate a SKU’s performance, a methodology it calls a “life rating.” This led to a weekly meeting where all SKUs are reviewed every other week (bath products are reviewed in weeks one and three, kitchen products are reviewed in weeks 2 and 4).

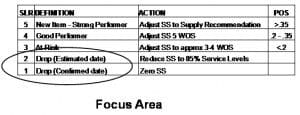

Carl was kind enough to send me a copy of his presentation slides. The diagram below shows how the company categorized its SKUs and the actions associated with the different categories.

The company’s definition of good SKU performance is based on store-level sales. For example, a strong performer would sell at a rate of over 0.35 units per store per week. But these rules are not set in stone. There is ongoing collaboration with sales and marketing on this process; for some SKUs sold to certain customers, there may be good reasons to make exceptions.

In conclusion, Carl made it clear that the rules were designed to provide parameters that would allow the company to “take action” instead of just saying, “We’ve got to watch that.” The company’s discipline paid off. In 2007, E&O cost Stanley Black & Decker 1.7 percent of sales. By 2009, it had fallen to 0.5 percent of sales, resulting in millions of dollars in savings per year.