Google is shaking up the GPS and navigation industry with some recent announcements. For example, Google is developing a map database to compete with the routing and navigation maps provided by NAVTEQ and Tele Atlas.

The company also announced it is offering a free turn-by-turn (TBT) navigation app with its Android 2.0-based smart phones (see video below and click here for more info and screenshots). Android is a “free” operating system for mobile devices developed by Google that competes with other mobile operating systems offered by Microsoft and others. Turn-by-turn navigation is in beta release, and it will take Google many months to develop its own detailed maps. Google’s goal is to monetize its navigation services by bundling them with advertising.

Google’s navigation efforts are currently focused on the consumer market, but these developments are worth monitoring by private fleet operators. The company’s vision is for users to dock an Android smart phone dock in their car, and instead of typing in a destination, they speak the location they want to travel to. Google’s vision is that the smart phone will provide not just verbal directions and a map, but also overlay the street map with satellite pictures and even street-level views. The maps will also show traffic congestion. The other nice thing about using an Internet-enabled smart phone is that you don’t have to periodically download current map data into your navigation device.

These smart phones will lack the capabilities of high-end telematics devices. For example, they won’t track a vehicle’s location or provide truck sensor data that can be used to improve fleet maintenance. I also wonder if satellite map and traffic congestion views will lead drivers to pay too much attention to the devices instead of the road.

Why does this matter to private fleet operators? There are both postive and negative implications.

On the positive side, Google’s investments in this area will drive down the cost of map data. If telematics and routing vendors use Google’s Geographic Information System (GIS) data, their costs would decrease and the fees they charge customers for their services could decrease as well.

Further, as more consumers use this service, the better Google’s live traffic congestion detection will work. When a consumer enables Google Maps with My Location, their phone sends anonymous bits of data back to Google describing how fast they’re travelling. Google then combines that person’s speed with the speed of other users on the road, across (eventually) thousands or tens of thousands of phones moving around a city at any given time. The application ends up with a good picture of live traffic conditions.

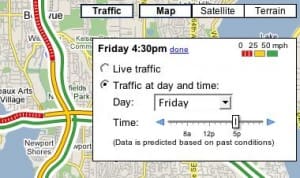

Once you have good historical data on traffic patterns, the next step is to predict traffic congestion. Using historical traffic data, a driver can see what traffic is typically like at any given day and time, making route planning easier. Do you need to drive to the Stop & Shop DC south of Boston? You can click the “Traffic” button in the corner of the map (it will only appear if traffic coverage for that area is available), and the traffic control will come up. You can then view average traffic patterns in the area for any hour and day of the week. Google is also moving towards displaying accidents, construction, and road closures in more urban areas.

There are also potentially negative long-term implications if Google’s free application is not reliable. Developing these detailed GIS maps will probably cost Google tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. Keeping them updated continually will require high on-going costs. If Nokia-owned NAVTEQ and TomTom-owned Tele Atlas abandon this market, and Google finds it can’t monetize these services in the way it had hoped to, the market for routing and navigation-based services could be left high and dry.

What is clear is that these technologies, and how they are used to support routing and navigation, are on the verge of big changes.