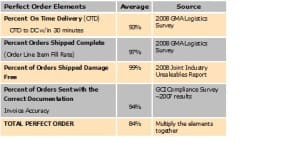

The perfect order metric (POM) is one of the most critical metrics in fulfillment.

The Warehouse Education and Research Council’s (WERC) definition of the perfect order metric is that a perfect order is delivered:

- Complete;

- On time;

- Damage free;

- And, with the correct documentation and invoicing.

This is tough to achieve a very high POM number because the final formula is based on multiplying the sub metrics together. So if the orders delivered in a time period averaged 99 percent complete, 99 percent on time, 99 percent damage free, and had 99 percent documentation (0.99 * 0.99 * 0.99 * 0.99), the final POM number for that period would be only 96 percent. And the worse the numbers you start with, the worse it gets. So if only 80 percent of shipments were on time and 80 percent were shipped complete, even if the company was perfect in the other areas, the total POM would only be 64 percent!

As if that is not tough enough, some large retailers have a far more demanding view of what a perfect order is. A paradigm shift is taking place in the fast-moving consumer goods supply chain. Large retailers are saying a manufacturer’s job is no longer done when the goods arrive at the retailer’s distribution center (DC). Instead, a manufacturer must now collaborate with its retail partners to ensure strong in-stock performance at the retail shelf, which ultimately leads to increased revenues and profits for both parties. The perfect order metric, as traditionally defined, is still important, but no longer sufficient.

But realistically, very few manufacturers have the ability to move toward a tougher view of POM that adds on-shelf availability of the product as one of the definition subcomponents; and the manufacturers that do have this capability tend to be a retailer’s category captains.

So let’s turn back to the traditional definition. I’ve asserted this a critical metric. It is critical because a strong performance on POM improves top line revenues. Many companies don’t want to do business with unreliable suppliers. In fact, some companies have quantified this. They have done studies to see how many POM mistakes it takes to lose a customer. Some have called the results “eye opening.”

Achieving a strong POM performance can, of course, increase fulfillment costs. If you have to hold more inventory to ship complete, there are costs associated with that.

Part of this depends on how a company defines a complete shipment. For example, imagine that a company tells a customer we don’t have that item, but we can ship the rest of the order, and the customer agrees to this. Then let’s assume the amended order is delivered “complete.” For some companies, this would not negatively affect the POM. Achieving this kind of order completeness does not require extensive inventory, just real time inventory accuracy.

Other companies are tougher on themselves. If a customer calls and they have to admit they don’t have an item a customer wants, this counts as a deviation that negatively affects POM. And this will certainly require more inventory. Moving from a 98 to a 99 percent inventory service level, requires exponentially more inventory than moving from a 90 to 91 percent coverage position.

In other ways, however, improvements in POM actually lower costs. For example, better warehousing processes that lead to fewer mispicks, and thus fewer returns, will almost always save money because handling returns is so expensive. Fewer returns also tends to drive a faster cash conversion cycle because customers are very slow to pay for orders that are being disputed.

In conclusion, I do think companies need to pay close attention to the perfect order metric. But it can be too simplistic, not to say unrealistic, to say our goal is a 100 percent POM score. The right POM goal will depend on a company’s competitive strategy. Those competing on service should strive for a very high score, those competing on price have a bit more latitude.

POM is a great metric but as you point out, very hard to achieve high numbers when multiplied. It is hard for a client in the 3PL world to contractually agree to a performance metric below 98/99%. If you have 5 metrics, with 99% performance on each, renders a 95.1% result; 98% on each renders a 90.5%. This is not the right metric to base an overall performance bonus on. Better to consider a collaborative maybe even a Vested contractual arrangement.

Perfect Order is a useful tool when properly used, but as Tim suggests, the POM needs to be used in the context of the elements which make it up.

It is a great guideline and stresses the importance of all related factors working together, but the parties involved must understand the math that Tim took us through. Additionally, some customers may want to weight the importance of one or more factors over the others, which can clearly skew the result.

Regarding shelf availability, this is a lofty goal. Most manufacturers have little visibility into shelf availability, and even less control. Most of my personal examples of shelf out-of-stock are immediately satisfied by store personnel moving stock from the ‘back room’ to the shelf. Hard to conceive of a supplier being dinged for the stores poor operation.

Metrics, and desired performance levels must be clearly understood and agreed to by all parties. And, they must be focuses on delivering improved customer and supplier satisfaction.