(Editor’s Note: This is Part 3 of a series of postings on labor standards. Click here for Part 1 and here for Part 2).

Discrete labor standards are more accurate than other types of standards, such as single and multi-variable, for several reasons.

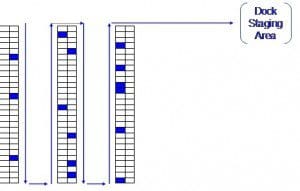

First, with discrete standards, travel time allocation is based on a warehouse map, which you can use to calculate the distance an associate travels from one pick location to the next, as well as the distance associated with a set of picks. Based on the travel distance and prescribed path, you can allocate time to that associate’s set of picks and the trip to the dock staging area.

The travel time allocation will depend on the type of material handling equipment being used (e.g., a cart, pallet jack, forklift, etc.). Developing standards for equipment requires more work than you might suspect. For forklifts, for example, you can conduct a time study to come up with a time factor that covers acceleration, steady state speed, and deceleration. A forklift might never reach full speed when the picker is in the aisle, but it could for the long trip to the dock.

The granularity of this type of time study can differ by consulting organization. Sean Adkins of West Monroe Partners, for example, said that many consultants apply a standard value for speed for a particular type of equipment, such as forklifts. But even for the same model, he says, there can be a 10 percent swing in speed. Also, tenured employees have a tendency to take the best equipment, which can add an element of unfairness to a labor management program. To further ensure a fair travel time calculation, they measure the loaded and unloaded speed of forklifts, delay locations (e.g., required stops at a cross walk), and the drop in speed when a forklift has to go up a ramp.

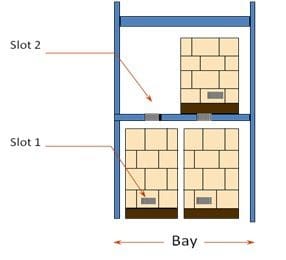

Thirdly, in contrast to the less detailed multi-variable standards, discrete standard are more likely to use actual case sizes and weights. The warehouse map knows the type of rack by location. The download file defines product size (cube) and the weight. A table is developed for the Labor Management System that classifies cases by relative size—Small, Medium, Large, XL—and where they will be pulled from in a rack. Time allocations will differ based on the cube and weight, as well as rack type and rack location.

Similarly, if the standard is for pallet picks or puts, time standards will differ based on whether it is a one-deep or two-deep rack, and where the pallet must be pulled (or put) from. Just as a fork lift is measured for speed, the speed with which the forks go up and down is also measured and factored into the calculation.

Finally, discrete standards can consider specific customer specific requirements—e.g., the amount of time it should take to put a label on a shipment to Walmart versus Target.

Because discrete standards are more granular than multi-variable standards, they are better suited for incentive programs. The typical goal of an incentive program is for the company and warehouse workers to split the productivity savings. If that is your goal, then you want to have tight standards that don’t allow workers to profit unless they really are working hard. Properly built discrete standards will also hold up in court challenges.

The main disadvantage of discrete standards is their implementation cost, which is much greater than using other standards because of the detail involved. Consequently, they are often too burdensome for smaller warehouses to use (those with fewer than 70 workers per shift, as a rough guesstimate).

In conclusion, after talking with different consulting organizations, it struck me that the granularity of discrete standards can vary. But very granular is not necessarily better. It costs time and money to go deep. Your consultant should have a sense of the risks versus rewards associated with developing a particular standard. In short, your consulting partner should continuously question if the effort of going deep is worth it.