At the end of January, two RFID suppliers announced that the European aircraft manufacturer Airbus will be using RFID tags to track thousands of components and parts for the A350 XWB aircraft models. Airbus had previously announced that if a part is serialized, repairable, and replaceable, it would require either an RFID tag or a contact memory button (CMB). In pressurized areas of the aircraft, RFID tags will be used. In unpressurized sections, however, Airbus said it will likely use contact memory buttons because of their greater robustness in harsh environments.

Waltham, Massachusetts-based Tego and Paris-headquartered MAINTag SAS have partnered to sell tags in the $10 to $30 per tag price range. The exact price will depend on the conditions the tags will need to endure, data capacity, and other factors.

This is clearly a different kind of problem than what Walmart and other large retailers attempted (and largely failed) to address with EPC tags, which sold for less than 20 cents per tag when bought in volume. Rather than a supply chain tracking problem—tracking the flow of goods from suppliers through retail distribution centers and eventually to the front of a store—Airbus is focused on tracking maintenance and safety issues. Airbus will use RFID technology to track the history of thousands of key components from the moment they enter the Airbus manufacturing stream, are placed on a particular jet, and all the way through the component’s product lifecycle. This asset lifecycle includes the component’s maintenance and repair history, right up to the time it is gets replaced with another part.

The usual way of tracking the genealogy of a part is to assign the component a part number on a barcode tag or through direct part marking. A production management system will often require a component to be scanned to make sure the finished product is correctly configured. The system also uses these scans to create the “as built” history. This history typically includes the installation date and even which production worker performed the installation. When subassemblies are purchased, this component-level tracking becomes more difficult because the supplier’s part number may not always correspond to the OEM’s numbering schema.

For the asset lifecycle, a different database is used. Every time a part is scanned as part of planned or unplanned maintenance issues, the data is entered in the “as maintained” portion of an Enterprise Asset Management system.

The fact that there are two databases makes it more difficult to trace the end-to-end genealogy of a part in the event of an accident. With RFID, much of the end-to-end genealogical history will be stored right on the chip. These are active tags that contain far more memory (up to 32 kilobytes) than the passive tags used in the retail supply chain. These chips can hold full documents, such as PDFs of diagrams showing the intended location of a part and other portions of a parts manual, the entire repair history of the part, and even the technicians involved in maintaining the part. After a faulty part has been removed, the data can help Airbus to track common problems, resulting in higher-quality planes being built in the future.

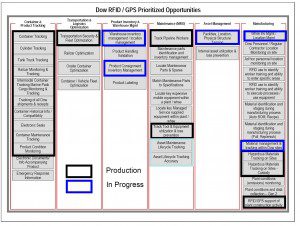

In summary, the Airbus program will deploy ruggedized high-memory RFID tags on flyable parts, allowing improved aircraft configuration management, repair shop optimization, spare parts logistics, and the monitoring of parts with a predefined lifespan.