For the past five years Terrapinn has organized an event called SCM Logistics World in Singapore. The event, which is taking place this week, is focused on supply chain management in the Asia Pacific region. Although I could not attend this year, I served as one of the judges for their Supply Chain Excellence award.

One of the candidates was a company that has made wonderful improvements in its supply chain. In fact, I consider this company to have one of the best-designed supply chains in its industry. However, in its application for the award, the company highlighted how it has shifted from a “demand push” environment to a “demand pull” one. The company considers itself “demand pull” because it has moved from production managers making whatever they wanted to fixed monthly production plans based on a demand forecast. From the company’s perspective, when production managers were producing what they wanted, it was “pushing” product into the market. Now a demand plan is “pulling” goods into the market.

If a company with a fixed production plan spanning a month is “demand driven,” or can be said to have a “demand pull” supply chain, then just about every company in the world can make the same claim.

The problem is that the term “push” has become pejorative, and it should not be. It is the right strategy for certain types of product value propositions. And despite its positive connotations, a “pull” supply chain is the wrong strategy in many instances.

As a former professor, I like things cleanly defined. To understand “push” and “pull,” it helps to understand the concept of a “push-pull boundary.”

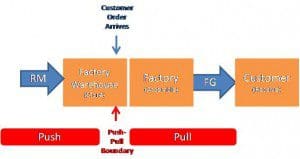

For most companies, some stages of their supply chain are operated in a push-based manner, while other stages are pull-based. The interface between the push-based stages and the pull-based ones is known as the “push–pull boundary.” The graphic below depicts a typical make-to-stock strategy. Based on a forecast, all the raw materials are acquired and finished goods are produced and stored. That is all push. The customer order denotes the boundary between push and pull. The pull part of this supply chain is based on sending the goods to the customer based on the order.

In the make-to-order supply chain, raw materials are procured based on a forecast, but the final product is not assembled until the customer order arrives. There is clearly more “pull” in make-to-order than in make-to-stock. In make-to-stock, if you forecast poorly, you end up carrying too much raw material and finished goods inventory. In make-to-order, you can end up with raw material inventories that are too high, but your finished goods inventories are lean. Because supply chain professionals hate inventory, there is a natural preference for make-to-order.

However, neither of these supply chains is pure pull. Only an engineer-to-order supply chain, where no raw materials are ordered and nothing is made until an order arrives, can be considered pure pull. Companies that make very expensive, highly customized pieces of capital machinery operate this way, but such supply chains are very rare. The fact that pure pull is so rare should serve as a warning that the “push” versus “pull” debate is too simplistic. Even Dell, the poster child for make-to-order, has become less pull based (its push-pull boundary has shifted to the right) since it began selling to large retailers.

I’ll end by giving credit to Sunil Chopra and Peter Meindl. The first time I came across the concept of a push-pull boundary was in a supply chain management textbook they wrote several years ago (a new edition was published in August).