In July the US, the European Union (EU), and select other countries instituted a number of trade and financial sanctions against Russia for its involvement in the separatist movement in neighboring Ukraine. The EU banned the export of military technology and certain technology used for oil and gas exploration and production in deep water, the Artic, and shale projects. In retaliation to these and other sanctions, Russia announced an import ban on food and agricultural products that the New York Times reported would include all beef, pork, fish, fruit, vegetables and dairy products from the US, EU, Norway, Canada, and Australia.

Courtesy of LLamasoft

(Click on Image to Expand)

I have read a number of articles analyzing and forecasting the likely economic effects from these trade sanctions. For example, the Russian supermarket X5 Retail Group is expecting slight price increases from the trade ban. And there are signs that the adversarial environment is taking its toll on the economic sentiment in Germany, as the ZEW indicator decreased to a 20 month low. Many of the economic concerns are amplified by the already unstable growth profile of the European economies, as these sanctions may be just enough to send the economies out of growth mode and into recession. However, it appears to me that much of the economic concerns surround the possibility of additional sanctions in the future. I also find the Russian ban on agricultural imports to be timely, given that it is harvest season in the temperate latitudes of the Northern hemisphere where Russia is located, and the country’s domestic produce can likely support its own needs for the next few months. Tim Worstall, the author of a Forbes.com article made the following comment that resonated with me (emphasis mine):

“The ban on imports of EU food into Russia doesn’t mean that the food will simply rot. Instead it means that there will be a shake up of trade patterns but largely the same amount of food will still be produced and also eaten, just specific types and production from specific areas will be consumed by different people.”

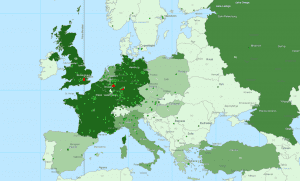

This statement largely captures why I believe that at least the Russian agricultural sanctions are primarily a supply chain disruption rather than an economic disruption. There are and will be economic damages to individual and groups of businesses. I don’t mean to downplay the economic harm. However, I do believe that businesses will adjust to the trade sanctions and this will be done primarily through supply chain adaptions. As Tim Worstall stated, in the medium term, food is “fungible,” meaning it is interchangeable. If Germany can’t sell its beef to Russia, but it can sell its Beef to Middle Eastern countries, and Middle Eastern countries can sell their beef to Russia, then Middle Eastern countries can export their beef to Russia and import from Germany. This specific example may occur to a limited degree, but I am using it to illustrate the point that supply chain networks will adjust, some trade lanes will become more congested, while others will become less utilized. I see this situation as a large, government induced supply chain disruption.

This situation really offers opportunity for supply chain network designers, logistics providers, and carriers to apply their skills to adapt to the new global trade constraints and match supply with demand. Robust supply chain scenario analysis can allow organizations to determine financially feasible opportunities to match their goods with buyers. Transportation providers can adjust their routes to meet shifting demand. There will likely be short term disruptions, but global supply chains will adapt, and astute logistics providers will see the opportunity to capture what is offered by newly created opportunities. And on a micro-level, in the short term, companies with fast and flexible supply chains will even be able to minimize the short-term disruptions.

Leave a Reply