T he phrase “retailer headwinds” caught my attention last week. I came across the phrase used by a number of sources that attributed soft comparable sales or difficult market conditions to these “headwinds.” The repetitive use of this phrase was especially relevant because I am currently researching the global warehouse automation market and the retail segment accounts for such a large percentage of global warehouse automation sales. In fact, ARC estimates that the retail sector accounts for over a third of total global warehouse automation sales.

he phrase “retailer headwinds” caught my attention last week. I came across the phrase used by a number of sources that attributed soft comparable sales or difficult market conditions to these “headwinds.” The repetitive use of this phrase was especially relevant because I am currently researching the global warehouse automation market and the retail segment accounts for such a large percentage of global warehouse automation sales. In fact, ARC estimates that the retail sector accounts for over a third of total global warehouse automation sales.

Last year there were some isolated signs of weakening demand for warehouse automation by retailers. For example, Daifuku reported weak sales to the retail sector in its most recent annual financial report. But for the most part, I considered that to be an anomaly, as other signs of robust demand appear to overshadow points of weakness from the retail sector. However, the transition to e-commerce is the primary driver of warehouse automation sales growth, and the overall health of the retail sector is essential to the continuation of this trend. So I decided to take a direct look at the health of the retail industry.

A Few Anecdotes

Companies such as Macy’s, Foot Locker, and Ascena Retail recently reported disappointing operating results that were attributed to “headwinds.” But what are these headwinds? Macy’s CEO is quoted in a recent earnings release stating, “We …will adapt our business in order to reach our goal of stabilizing the brick-and-mortar business while investing for accelerated growth in digital and mobile.” Foot Locker attributed its recent reduction in sales to a number of factors, including limited new product availability. But at the same time, the company’s Athletic Stores sales declined while its Direct-to-Consumer business grew. There have also been intermittent reports of shopping mall vacancies and the sporadic retailer bankruptcy (have you noticed that seasonal Halloween stores tend to occupy these spaces?). But it is difficult to determine if vacancies are accelerating or if the demand for retail properties is simply shifting.

What Does the Economic Data Show?

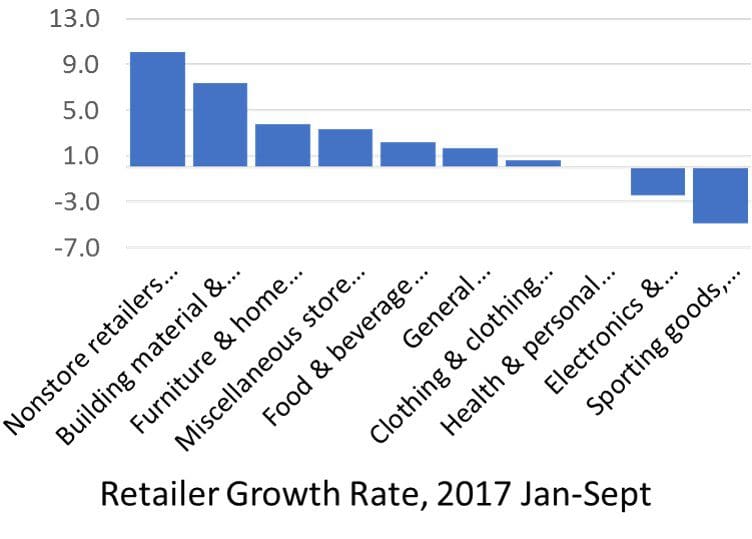

The US Census Bureau reports monthly retail sales, but these top-line numbers include some data of little relevance to warehouse automation (gas station sales, for example). So I reviewed the most recent data and removed motor vehicle, food service, and gasoline stations. This revised retail total amounted to almost $2.5 trillion for the first 9 months of 2017. Non-store retailers accounted for 18 percent of these sales. And at 10 percent growth, these retailers achieved the highest growth rate of all sub-sets within the retail sector (non-store retailer growth amounted to $40 billion for first nine months of 2017). Therefore, non-store retailers are causing an approximate 2 percent drag on the growth of other retailers, if you assume that non-store retailers’ growth is at the expense of the brick and mortar retailers. At the same time, its worth noting that 60% of sales of non-store retailers are categorized as e-commerce, whereas 7 percent of total retail sales are categorized as e-commerce (2015 data). Of course, this is US data, and ARC’s research on the warehouse automation market is global. At the same time, retailer sales do not amount to capital spending trends, never mind capital spending on warehouse automation. But it’s fair to say this may be representative of the industry as a whole. Regardless, I plan to look deeper into retailer capital spending trends.

Conclusion

This quick analysis leads me to believe that the retailer headwinds are very much a result of the transition from brick and mortar retail toward increased e-commerce business. At the same time, I do not see evidence that this trend will have a negative impact on warehouse automation sales to the retail industry. In fact, this may be indicative of an acceleration in retailers’ investments in their e-commerce businesses and fulfillment operations, and away from their brick-and-mortar operations.

Leave a Reply