In my “What Causes Shelf Out-of-Stocks?” posting last week, I reviewed some research conducted by Walmart on the major causes of shelf-level out-of-stocks. One reason, occurring about 20 percent of the time, is phantom inventory. Phantom inventory occurs when the store system shows inventory available but none really exists. It also occurs when the system shows more inventory than what is actually available in the store; this can be caused by theft, broken products, mis-picks or checkout issues, for example.

When a store system shows inventory that doesn’t really exist, a store manager could easily assume the product is not selling well and thus decide not to reorder it. When the store system shows more inventory than what really exists in the store, this can also create havoc. I did not fully understand why this was so until Cedric Guyot of Retail Solutions walked me through some slides and explained it to me.

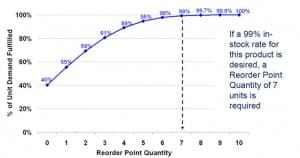

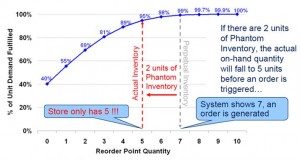

Stores have min/max replenishment logic just like other nodes in the supply chain. Imagine that for a particular SKU, the min is seven and the max is fifteen, and that the store reorders every time the inventory level falls to seven or lower. When the store reorders the product it makes sure the delivery will bring the number of items in the store up to 15. These min/max targets are based on a service level analysis – e.g., the minimum target level that will lead to a 99 percent in-stock rate for that product. In other words, with this minimum target level, if the store operations folks do a good job of keeping the shelf replenished and the inventory accurate, there is only a one percent chance, based on the demand history of that product, that a customer will not find this item in stock when they want to buy it.

Now assume that there is some phantom inventory, that there are two less units of inventory in the store than what the system shows. As the chart below shows, the target service level for a min of 5 is only 95 percent. So, if this min reorder point had been chosen, customers coming into the store would not have found that product in stock five percent of the time. Further, if you look at the shape of the service level curve, the more units of phantom inventory, the greater the drop-off in service level. If the store inventory system says there are seven units of the product available, but only two really exist, the service level would be only 69 percent. The shape of this curve is pretty typical. The more phantom inventory you have, the easier it is to have truly unacceptable, yet hard to detect, shelf service levels.

Finally, when the level of phantom inventory becomes greater than the reorder point quantity (eight in the above example), the store stops ordering altogether, creating long out-of-stocks that can only be fixed by an inventory adjustment.

I should point out that the service level curves shown above are hypothetical. Store-level SKU service levels would differ for every SKU in every store based on that store’s/SKU’s demand history.

In conclusion, Mr. Guyot tells me that most studies show 40 to 50 percent of the items in a store have some amount of phantom inventory. This is clearly a serious problem, but a problem that current Demand Signal Repositories are helping to solve.