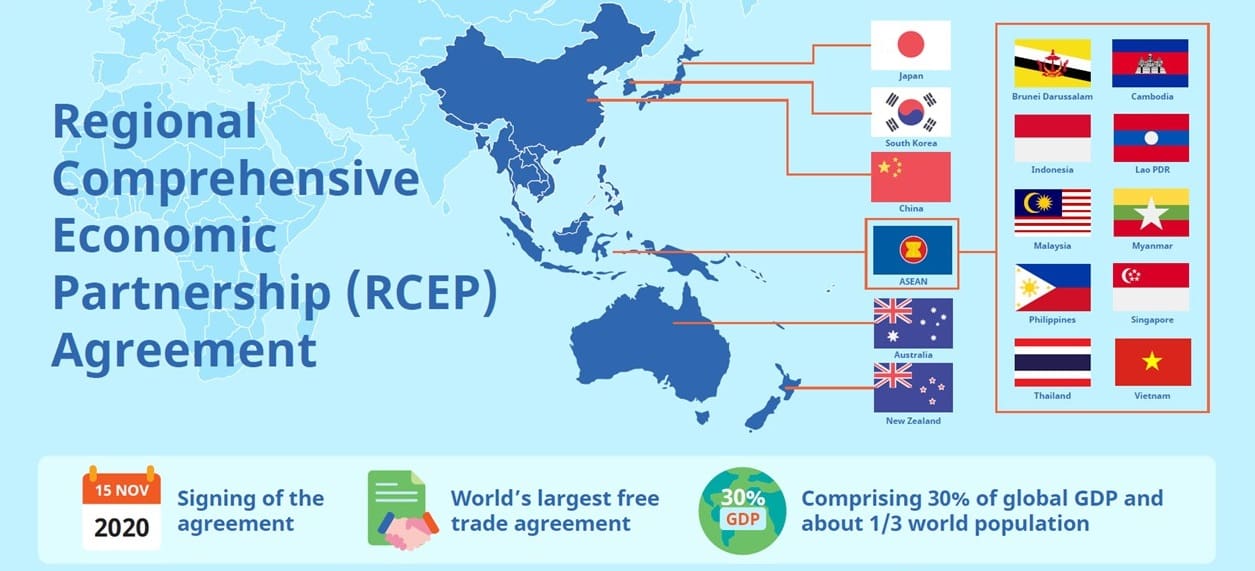

First conceived at the 19th ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) Summit in Bali, Indonesia, way back in 2011, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) finally came into fruition on November 15 at this year’s 37th ASEAN Summit. In line with these pandemic times, while the ASEAN meeting was nominally held in Hanoi, Vietnam, it was a virtual signing ceremony that saw 15 countries in Asia Pacific become part of what is now the world’s largest free trade agreement, representing 30 percent of global gross domestic product and encompassing almost 2.3 billion people. The 15 member RCEP countries comprise the 10 nations of Southeast Asia; China, Korea, Japan in north Asia; and from down under, Australia and New Zealand.

Based on computer simulation analysis done by Peter Petri (Brookings Institution) and Michael Plummer (Johns Hopkins University), RCEP has the potential to add an annual $500 billion to world trade and $209 billion to world incomes by 2030, as economic linkages strengthen in the region, notably for those members without existing bilateral FTAs, e.g. China-Japan and Korea-Japan, and the bloc becomes a more attractive entity for global trade.

Key FTA Elements

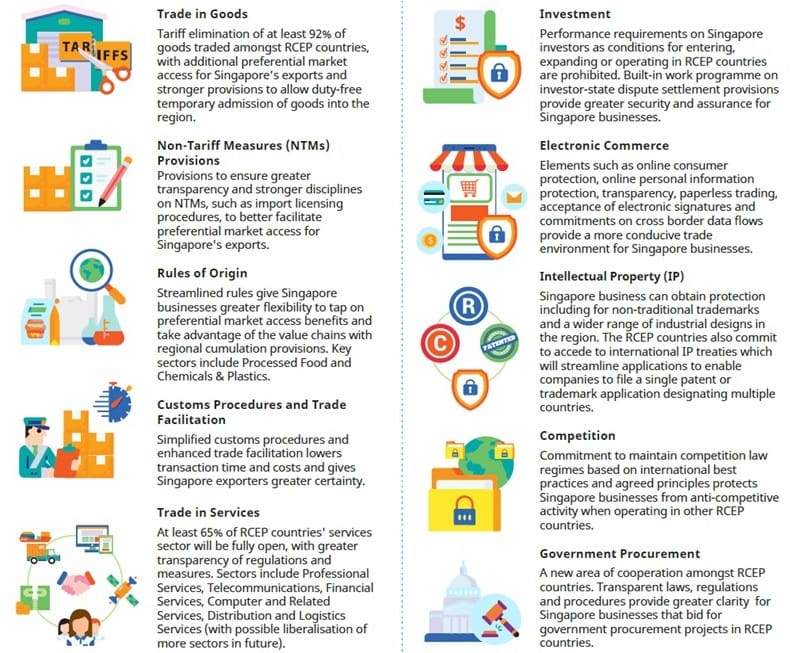

As a free trade agreement, several aspects of RCEP aim to facilitate the flow of goods between RCEP Participating Countries (RPCs). These include: tariff elimination on at least 92 percent of goods traded between RPCs; simplified customs procedures to expedite the clearance of cargo, with a six-hour ceiling for express and perishable items; and easing of rules of origin definitions.

This last item, rules of origin (ROO) is particularly significant as it means that a product can be shipped at the most preferential tariff rate to any of the 15 RCEP markets as long as it contains content produced in any one of these countries. Previously, companies, notably those in the chemicals, consumer product goods, and food & beverage sectors, may have had to alter ingredients and formulations in order to ship preferentially to different markets within the bloc.

Beyond free trade goods provisions, RCEP mandates the opening up of domestic service sectors, including those of telecoms, financial services, and distribution and logistics, to overseas suppliers, with a target of 65 percent of services sectors to be fully open. Cross border investment also becomes easier through eliminating the need to comply with conditional performance requirements.

Further business-friendly provisions in RCEP include those for raising the standard of IP protection, discouraging anti-competitive activities, and facilitating e-commerce e.g. through the acceptance of cross-border electronic signatures and paperless trading. And to open up often lucrative government procurement opportunities to the region, RPCs will be required to be more transparent in terms of the procedures involved in bidding for government contracts.

India: Missing in Action:

Not surprisingly, with RCEP comprising a diverse group of members, ranging from advanced countries like Australia, Japan and Korea down to the still very much developing nations of Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar, the road to the 20 chapter, 14,000 page agreement was long and sometimes arduous. While the members had to deal with complications such as changes of governments and spats between countries, such as the recent COVID-19 blow-up between Australia and China, the decision by India to exit RCEP discussions in November 2019 was a significant late disruption.

With the country already running trade deficits with almost all of the RPCs, it was fears of a surge of imports, especially from China, that figured prominently in its decision to withdraw from negotiations. Although there is no sign of any change of heart by the Indian government, the official RCEP statement during the November 15 signing ceremony held out an olive branch by articulating a “strong will to re-engage India in the RCEP Agreement” and extending an invitation for India “to participate in RCEP meetings as an observer and in economic cooperation activities…on terms and conditions to be jointly decided upon by the RCEP Signatory States.”.

Free Trade Back in Fashion

The press announcements made by the various leaders of RCEP nations to accompany the signatures to the agreement are notable for their distinction from the Trump-era bashing of FTAs where trade was seemingly a battle is a to be fought − with winners and losers − rather than a global good.

For example, PM Lee Hsien Loong of Singapore: “At a time when multilateralism is losing ground, and global growth is slowing, the RCEP shows Asian countries’ support for open and connected supply chains, freer trade and closer interdependence.” Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison: “With one in five Australian jobs reliant on trade, the RCEP Agreement will be crucial as Australia and the region begin to rebuild from the COVID 19 pandemic.” And Chinese Premier Li Keqiang: “The signing of the RCEP is a victory of multilateralism and free trade. Let people choose solidarity and cooperation when facing challenges, instead of resorting to conflict and confrontation.”

Of course, the proof is in the proverbial pudding, and there are legitimate concerns over whether China will come to adversely dominate the new grouping, and domestic ratifications still need to proceed before the RCEP Agreement formally enters into force. Still, after almost a decade of discussions, latterly against a backdrop of rising protectionism, and with seven RCEP members also embroiled in the on-off-on saga of the TPP/CPTPP for much of the time, the eventual realization of this new economic partnership bodes well for the continued growth of the Asia Pacific region and for the ethos of free trade.