Starting in September 2019, Walmart and its Sam’s Club division will require their suppliers of fresh, leafy greens to implement real-time, traceability of products back to the farm by participating in the Food Trust Consortium. The Food Trust consortium, run by IBM, is focused on using Blockchain technologies for improved food traceability.

In addition to leafy greens, Walmart plans similar mandates for other fresh fruit and vegetable providers within the next year, according to Frank Yiannas, vice president of food safety at the world’s largest retailer. “It’s becoming a business requirement, it’s a part of our supplier agreements,” Yiannas said in an interview. The goal is to speed up response times in cases where food-borne illnesses force recalls. Starting with salads and fruits is logical. These foods are consumed without cooking. Bacterial contaminates like salmonella are killed during cooking. Contaminates on items consumed without cooking are particularly vulnerable to a recall.

A critical question is whether the mandate will have legs. Walmart imposed a RFID mandate on their 100 largest suppliers in 2005. I talked to over 50 of those suppliers at that time. The supply chain executives saw the mandate as providing value for Walmart but being counterproductive for them. They believed the initiative provided little value to their supply chains but was certain to increase their costs. Not surprisingly, the RFID mandate failed.

In August, I got details from IBM’s Suzanne Livingston, Offering Director, IBM Food Trust and Ramesh Gopinath, VP Blockchain Solutions, about how the Food Trust solution works.

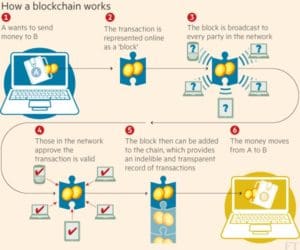

Architecturally, this is a distributed system; in other words, a system that runs on multiple nodes in multiple data centers. The nodes are run by “trust anchors” – basically, some of the largest companies in this end-to-end supply chain. A blockchain involves having copies of the transactions being stored across the different database nodes. IBM believes that a few dozen nodes are necessary to establish a trusted chain of data.

GS1 standards are used to make sure all participants are speaking the same language. But in addition to providing the hardware, software and Cloud components, insuring that the data is clean and logical is a big part of what IBM brings to the table. Some players in the food supply chain will provide serialized numbers at the case layer, some at the pallet level, and some only at the lot level. “Not everyone is at the same level of maturity,“ Mr. Gopinath stated. “There are data gaps.”

It is not clear what Walmart is demanding of their suppliers, but in August IBM’s view was they just wanted new participants to give a bare minimum of data to get started on a trace. “Then we will work with companies to grow their maturity.” It is likely that once companies get started, some participants in the value chain will want additional information. For example, retailers may want to know whether refrigerated products were kept in the proper temperature range and may also want visibility to in transit information. A food manufacturer may want to know how much product has been received at myriad different stores in a retail chain.

IBM is taking an interesting approach to pricing the solution. Companies that want to join the Food Trust, will be able to provide traceability data for free. These companies will need to inform IBM on who they are, the products they want traced, and who they will be interacting with from a one up, one down perspective. That company may need to do some work to understand the GS1 standards, make sure they can provide clean data, and figure out how that data will be sent to the blockchain.

IBM seeks to monetize their effort by charging to display analytics information, for example statistics on the timeliness and quality of transactions provided to other members of the chain. And IBM will charge a subscription fee to share certificates. For example, a farmer may claim that they offer organic strawberries. An auditing firm verifies this, and IBM charges for uploading the organic certification to the blockchain.

While the initial focus is traceability, the solution could easily grow into something much bigger. Mr. Gopinath pointed out that this is a platform for sharing information. Initially that shared information is focused on traceability, but “food waste, food fraud, food safety issues are all related to problems with effectively sharing information. We want to leverage by third parties to deliver more value to the ecosystem.”

Will this mandate have legs? If the initial plan is followed, and suppliers’ costs for participating are minimal and they are allowed to walk before they run, it will achieve supplier acceptance.

But the question then becomes, how much does it increase Walmart’s costs? Once the retailer starts to generate data they will have to see how increased costs surrounding Food Trust are balanced by lower costs in recalls; how much prices for produce will need to increase; whether those price costs can be passed along, and similar cost/benefit trade off questions. In short, the viability of Blockchain for traceability is not assured yet, despite the mandate.

Blockchain for Supply Chain Management will be discussed at ARC’s upcoming Driving Digital Transformation forum February 4th to the 7th in Orlando.